Darasingh | Mandala Theatre | Folk performance | Political rebellion | Limbu history

“As of now, Karnahaang will be known as Darasingh and is pardoned for the Faujdaari on account of his death.”

The stage fades to black, followed by the radio’s broadcast of Karnahaang’s death, announcing him as Darasingh—a name symbolically meaning strength and valor. You may have heard this name from a character playing Hanuman in Ramanand Sagar’s epic Ramayana but in Far Eastern Nepal, Darasingh carries a different legacy—a mythical rebellious character known for his valiance.

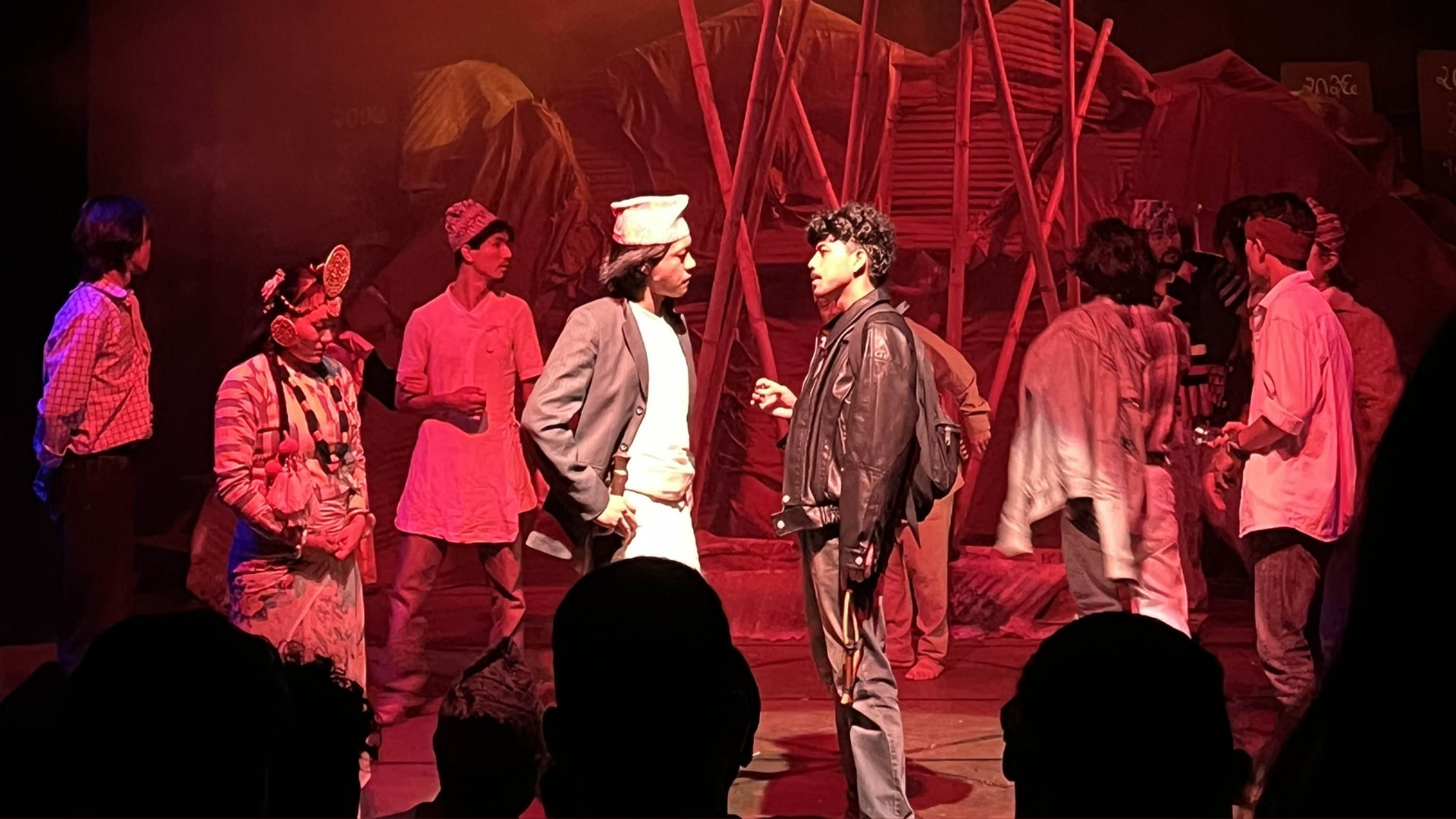

Mandala theatre’s oral historic play Urf Darasingh is a reminiscence of the country’s unique cultural roots and disparate values and beliefs. Revolving around the revolutionary perspective of this common man, Karnahaang Kerung amidst the socio-political turbulence in Nepal—the play depicts the story behind Darasingh.

Set against the backdrop of the 1960s, the play begins with a tribute to the Mai Khola and Tamor Khola’s romantic folklore. From there, it delves into the complexities of Eastern Nepal’s land tenure system and the political unrest during the Panchayat system. For someone who’s unfamiliar with Jhoda, Satta Bharna and the abolishment of land rights of the Limbus during the 60s, some scenes and symbolic relics may be difficult to follow.

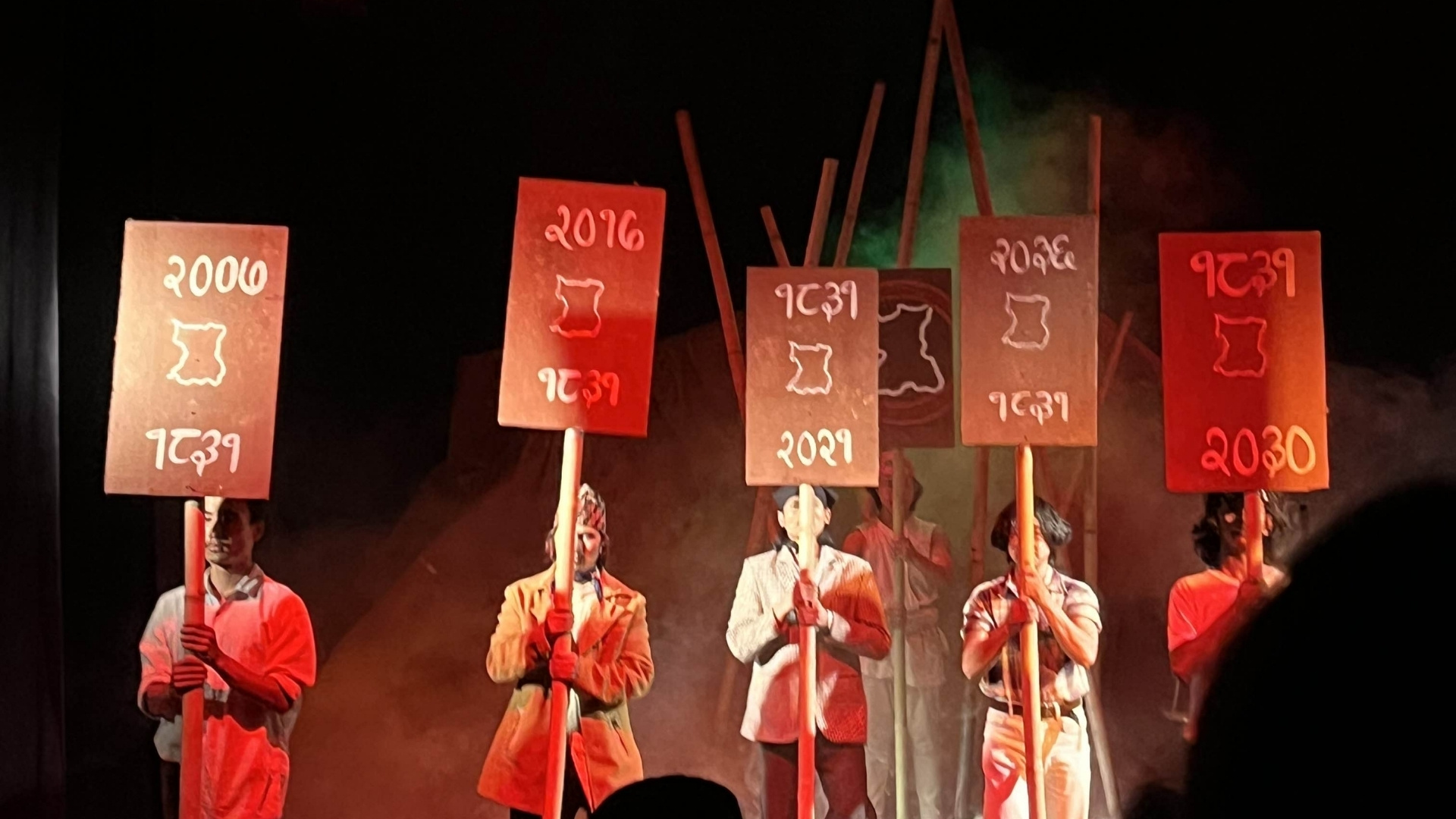

In 1964, King Mahendra abolished Kipat—the communal ownership-based land tenure system practised by Eastern Nepal’s Limbus, Yakha, and also Bhotes and Majhis—through a second amendment in the Land Reform Act. It was replaced by a new land tenure system, Jhoda [also termed Jhora in the Dhimal language] which means a stretch of forest area between two rivers. The tribal communities were given this stretch of land for settlement.

In the play’s first half, a government notice with the slogan Ek Jaati Ek Bhes, Ek Raastra Ek Desh declares Satta Bharna—compelling the tribe to migrate in the name of Northeast’s development while offering land compensation. Tribal members get agitated with this as they had previously made similar promises, leading to a ruckus. Karnahaang tears the government papers and finds himself in trouble over this.

Although Karnahaang is a rebel in nature, the play also sheds light on his family and community life. He shares the household burden of his wife and collaborates with Kancha Subba in opening a school in their village to promote their culture’s manuscript.

Yet, the corrupt Panchayat officials see him as a nuisance for his rebellion against Satta bharna. They plot against him and every other person involved under Faujdaari (criminal) offence.

The plottings against Karnahaang are well depicted through the imaginative ‘Baghchaal’ themed staging. Similarly, the play exhibits strong authenticity of Far Eastern culture. The frequent mention of Maang—a benevolent deity protecting and guiding the community—the sacrificing rituals, and how Limbus address their kinship are well executed.

The presentation of the 60s setting is also phenomenal—subtly expressed by radio playing melodies of Mohammad Rafi. The characters show quotidian routine impressively—with characters engaging in livestock rearing, farming and bartering rations.

Parallely, we witness internal conflicts in Karnahaang, intensified by the memory of his parents, whom he lost during the Kipat rebellion. While the Paalam scene (a Limbu folk song where a girl and a boy engage in a question-and-answer session) and Karnahaang claiming an already married woman demonstrate his flawed persona. And as tension rises and a brawl occurs during this specific episode, it serves as a premise for deeper character development across the ensemble.

There is a sleek and fascinating depiction of forthcoming events—such as Karnahaang’s death mirroring a supporting character’s dream and an ominous cry of a household pig. In contrast, humour shines with one-liners and playful banters, providing an entertaining relief.

The casts enacting the play are commendable in their performance. Aakash Suhaang’s balanced portrayal of Karnahaang has emotional depth. Man Kumar Yonghaang as Khambasingh/the local trader stands out as a Khamba, especially in a scene where he shows his wrath during confrontation with Karnahaang. Characters like Adakshya Ji, Hawaldaar, Kharlambe, Thette, Tumyahaang, and Aangdambe, keep the audience’s engagement intact with their monologues and interactions.

Karnahaang, urf Darasingh, is a character adherent to his ideology. He finds himself politically targeted for his advocacy on good governance and leading linguistic freedom. Director Chetan Anghtupo’s attempt at presenting a different side to the same coin is applaudable—from Karnahaang’s personal crisis of conscience to political events and failed leadership that led to his rebellion.

Read More Stories

Kathmandu’s decay: From glorious past to ominous future

Kathmandu: The legend and the legacy Legend about Kathmandus evolution holds that the...

Kathmandu - A crumbling valley!

Valleys and cities should be young, vibrant, inspiring and full of hopes with...

A hidden glacier lake caused the deadly Bhotekoshi flood, scientists say

The catastrophic Bhotekoshi flood, which wreaked havoc in Rasuwa last Tuesday killing nine...