Air pollution | South Asia pollution | Public health | Clean air policy

Toxic haze engulfed Kathmandu for days this April, part of a now-annual event that drives the city’s pollution level to alarming highs each year. Across Nepal, other regions are also grappling with this annual surge in haze and decline in air quality.

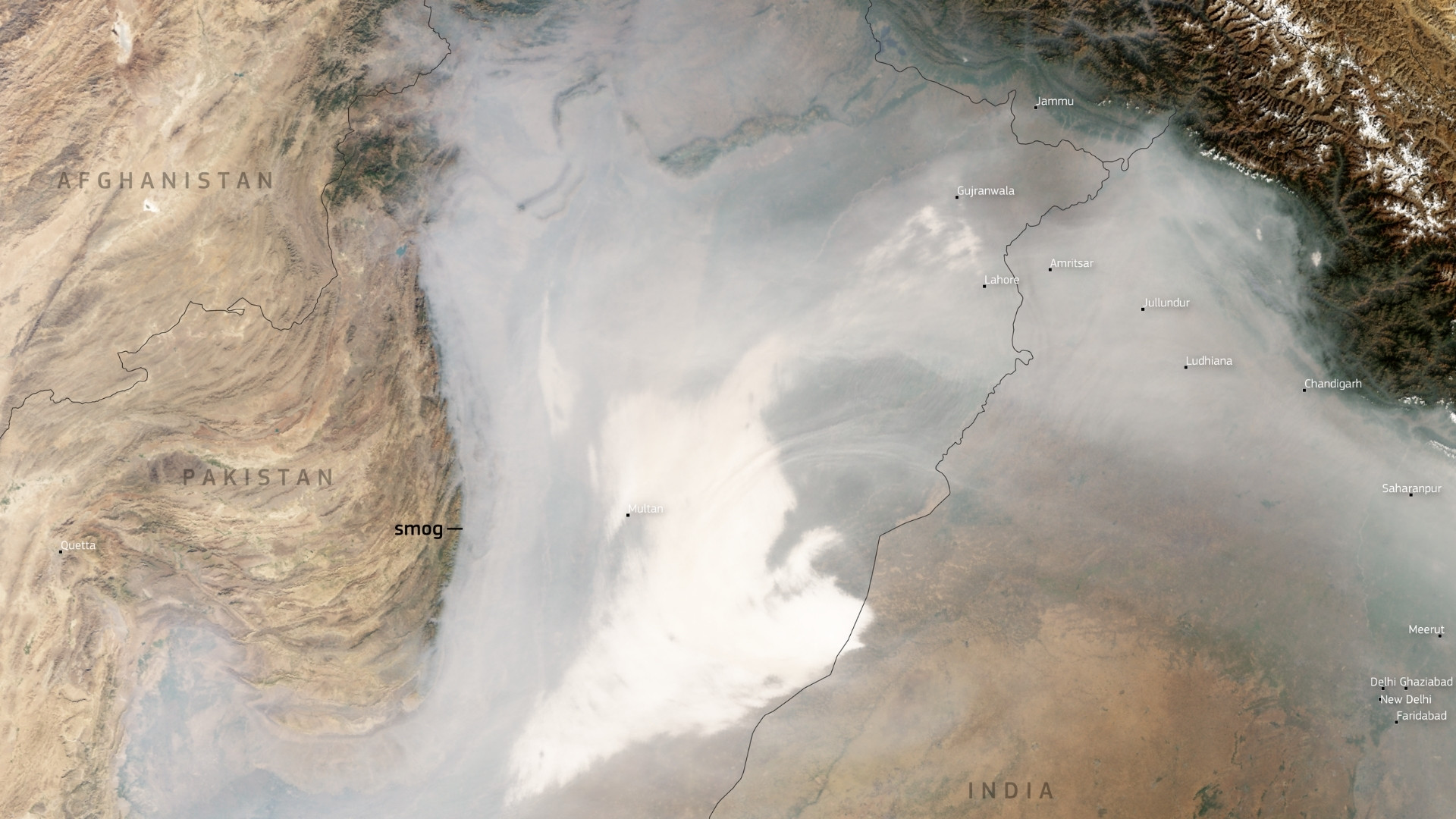

While pollution in Kathmandu makes headlines, the level of air pollution, particularly much higher levels of PM 2.5 in Nepal’s Terai, hasn’t garnered much media attention. The Indo-Gangetic plains have the highest level of air pollution globally, making their air quality one of the greatest threats to human security in South Asia. Data shows nine of the ten most air polluted cities are from this region.

Public health and economic impacts

The persistent haze has generated several problems, ranging from low visibility impeding air and land traffic mobility to serious public health hazards from allergies to respiratory diseases. Air pollution is estimated to result in 2.6 million deaths across South Asia in 2021.

PM2.5—airborne particles with a diameter of 2.5 micrometres or smaller—is considered the most harmful air pollutant. Due to their tiny tiny size, these particles can bypass the body’s natural defenses, infiltrate deep into the lungs, and enter the bloodstream, causing cardiovascular and respiratory disease and cancers.

Meanwhile, a study shows if Nepal's air quality is to meet the WHO guidelines, it could boost the population's life expectancy by 3.35 years on average. Madhesh province can make the highest potential gains in life expectancy up to 5.08 years, with gains in Rautahat district being as high as 5.33 years. Similar gains are also expected across South Asian countries: 3.32 years in Pakistan, 3.57 years in India, and 4.82 years in Bangladesh.

Additionally, air pollution is disruptive to the country’s tourism potential. Haze is no longer a city problem—but emerging in the high Himalayas as well, where mist and haze obscures mountain views. Air pollution and haze contradict Nepal’s image as a natural paradise, interfering with the picturesque landscape along with visitors' health.

The incoming tourists and the country’s tourism industry are increasingly expressing concerns about the country’s worsening air pollution, an issue that’s also drawing widespread international media attention. This is highly likely to induce shorter visits, cancellation of future plans and deter potential tourists altogether. More importantly, it threatens to stall the revival of an industry that’s still struggling to find its footing post-pandemic.

Other South Asian cities and tourist destinations are also facing similar problems. Reportedly, the total cost of air pollution to the Indian tourism industry is estimated at $1.7 billion. Apart from that, air pollution also reduces workers productivity and causes cognitive impairment.

Major sources of pollution

Indigenous sources of air pollution, consisting of forest fires, transportation, cooking fuels, brick kilns, and other industries, have been significant polluters.

Every year, about 5,000 forest fires around Nepal plummet the air quality, most of them occurring between January and June. Besides, forest fires also damage Nepal's economy, ecology, and overall well-being of the Nepali population.

Moreover, transportation-resuspension of dust particles due to vehicular movement and vehicular tailpipe emissions also contribute to air pollution, mainly in the urban centers.

Brick kilns are another major source of air pollution. About 1,600 brick kilns burn about 1 million tonnes of coal in Nepal. They alone are responsible for about 28% of PM-10 concentration and approximately 40% of Black Carbon emissions in Kathmandu Valley during winter.

This challenge is not unique to Nepal. Across South Asia’s ‘brick belt’ with more than 120,000 brick kilns, they are a significant driver of air pollution. These kilns emit large quantities of black carbon and other greenhouse gases, accounting for up to 90% of particulate matter pollution in some South Asian cities.

Besides impact on visibility and public health, black carbon also increases the rate of glacier melting in the Himalayas by absorbing solar radiation and raising the surrounding temperature, which is detrimental to the water availability for billions residing in the region.

In Nepal, apart from its domestic sources, the country is also affected by transboundary pollution. As mentioned earlier, South Asia, extending from Eastern Pakistan to Northern India, Southern Nepal, and Bangladesh, forms one of the most polluted regions in the world, with pollutants often crossing national borders and compounding air quality problems.

There is clear evidence that wind pushes the pollutants generated in the Indo-Gangentic plains even into higher Himalayas, with trans-Himalayan valleys serving as critical pathways for this movement. During post-monsoon, as Agricultural Residue Burning (ARB) happens in North Western India, Kathmandu Valley, Terai districts, and other places in the Central Himalayas witness a rise of PM 2.5 to a hazardous level.

These transboundary pollutants, which are emitted throughout the post-monsoon season, accumulate in the Southern Mahabharat ranges and aided by favourable wind move to Kathmandu and other places in altitudes as high as 4,000 meters in the Himalayas.

Transboundary pollution, diplomacy and geopolitics

Multiple sources of air pollution and their transboundary nature highlight the need for multi-sectoral and multi-scalar efforts to tackle air pollution in Nepal.

Air pollution in South Asia is a regional problem that demands a regional effort, as Nepal's effort, while necessary, is not sufficient on its own. As a downwind nation, Nepal bears a disproportionate brunt of transnational pollution and its other effects. This has led many to call for Nepal’s engagement in ‘haze diplomacy’ with India and Pakistan for regional collaboration.

Given that the country hosts the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) and the International Center for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD), it is well positioned to lead for a regional solution. However, little is discussed about the complexities of such a regional solution based on cooperation in the geopolitically charged environment of South Asia.

While transboundary pollution and haze have not yet caused any diplomatic row in South Asia—as in ASEAN countries—largely due to the region’s focus on pressing geopolitical issues, the severity of the transboundary haze is impossible to ignore. Yet air pollution remains out of priority for government authorities, while citizens have come to accept pollution as a part of their lives, reflecting a shared complacency on both sides.

There are some efforts though. Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Nepal, Maldives, Iran, India, Bhutan, and Bangladesh adopted Male Declaration on Control and Prevention of Air Pollution and Its Likely Transboundary Effects for South Asia in 1998, creating an intergovernmental network.

The Male Declaration acknowledged the threat, focused on the need for a coordinated effort, and envisioned each signatory implement different programs on a phased approach, which included research and studies on air pollution, awareness generation, and capacity building. There was progress, but the problem in the region has intensified instead of abating. This slow progress should not be interpreted as a sign that regional cooperation is futile but rather as a clear indication of urgency for greater, stronger and meaningful cooperation, coordination, and decisive action.

Why do regional agreements fall short?

International law upholds the principle of state responsibility, affirming that countries have a duty to ensure that activities within their jurisdiction do not cause environmental harm to other states—where the 1972 Stockholm Declaration and the 1992 Rio Declaration on Environment and Development have been influential in shaping global environmental policies and frameworks for minimising transboundary harm.

Based on these declarations, states have adopted cooperation and prevention regimes. However, implementing principles like state responsibility and civil liability has proven challenging worldwide. Experiences from other Asian regions like ASEAN demonstrate that such regional engagement often falls short of achieving desired change, even in a relatively favourable geopolitical environment.

In Southeast Asia, haze and transboundary pollution are heavily politicised issues and often cause diplomatic disputes. Joint efforts between ASEAN countries began with the 1997 Regional Haze Action Plan (RHAP) and the 2002 ASEAN Agreement on Transboundary Haze (AATH) five years later.

The AATH has provisions for a task force on Peatlands along with a joint ASEAN Haze Fund to aid its implementation. Despite being legally binding and comprehensive, it has failed to create a conducive environment for addressing the transnational haze. State responsibility and civil liability have been difficult to enforce due to the strong endorsement of the principle of non-interference in the ASEAN Charter. States are reluctant to negotiate with the international regimes for liability of transboundary harm caused by air pollution due to political and financial reasons. As a result, efforts have often devolved into a blame game, increasing political tensions.

The patron-client relationship prevalent in Indonesia (where most of the forest fires occur) and other Southeast Asian countries is one cause of continuing air pollution. Government and political patrons often protect their business clients who engage in polluting activities from scrutiny and punishment, enabling them to function with impunity.

The patronage is often extended across borders, and the countries tend to shield their companies operating in foreign countries from pollution charges. Similarly, national pride also comes in the way of successfully tackling pollution, as countries blame each other for the problem.

Similar issues will be evident while tackling transboundary air pollution through regional efforts in other regions of the world. For instance, within India, different states blame each other for the air pollution. Every year, the Delhi government blames the burning of agricultural residue in neighboring states Punjab and Haryana for the hazardous air pollution level. The blame game between states within a country speaks volumes about the intractable nature of the problem. When a significant portion of air pollution travels from India to Pakistan and vice versa, it is unlikely these politically hostile nations will cooperate.

In such a context, Singapore has taken a bold step through the Transboundary Haze Pollution Act (THPA) in 2014 to address forest fires from neighboring states like Indonesia and Malaysia. It allows Singapore to take legal action against foreign entities if their activities, even in foreign countries, cause pollution in Singapore. This is expected to push companies operating in the region to take strong steps to prevent, control, and mitigate pollution.

Replicating such a model in South Asia is however challenging. Unlike Singapore, which holds great regional economic influence as a financial hub, the most important South Asian countries, which are also the largest polluters, lack deep economic integration. On the other hand, smaller countries like Nepal, Sri Lanka, and Bhutan lack the political and economic leverage to enforce environmental laws on domestic and foreign entities.

A call to action: Making clean air a public priority

Some believe air pollution will resolve once a country achieves higher levels of economic growth. This perspective is often supported by proponents of the environmental Kuznets curve, which argues that environmental degradation will increase till a certain level of income is reached, after which improvement will occur. This means pollution and economic development go together to a certain level.

While the evidence from China and some Indian states provides credence to this hypothesis, the reality in neighboring Indian states like Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, West Bengal, and Punjab indicates that the real turning point is still far off. It’s crucial to recognise the toll of air pollution on public health and labor productivity—and that clean air is not a constraint but a catalyst to growth and productivity. Well-designed measures can spurr green growth rather than hindering economic development.

Air pollution is a complex, deeply entrenched challenge demanding coordinated actions across all levels of government, society, and borders. While curb on domestic emissions must be intensified, the call for haze diplomacy can ring hollow owing to the current regional geopolitical state and Nepal’s declining clout in the international arena over the years. Yet harmonising pollution standards across different countries in the region can be a good start. Even a government report concedes that Nepali pollution standards for brick kilns are laxer compared to neighbors in India and China.

While Nepal’s federal government has a crucial role, meaningful progress will only come when provincial and local governments actively contribute. A key lesson can be derived from China, where local and provincial authorities initially prioritised growth over environmental health. But mounting pressure led to a shift. Officials are now rewarded based on green performance indicators like “green GDP,” emphasising sustainable development over unchecked growth.

The approach has helped to spur growth and development of new environmentally friendlier energy technologies. Nepal and other countries must adopt a similar approach by developing an environmentally inclusive performance index to evaluate and incentivise sub-national governments.

Yet, it is naïve to believe that the government alone can solve this crisis. Global experience shows that combating pollution requires a democratised, multi-stakeholder effort. The private sector and civil society must be empowered to lead alongside the state.

In Nepal and countries across South Asia, air pollution has yet to spark public outrage and become a significant election issue despite being one of the leading causes of premature deaths. The complacency must end. Civil society can raise public awareness, demand accountability, and drive air pollution onto the political agenda.

Civil society activism and politicisation of the pollution issue can help lay bare and fight the patron-client relationship deeply entrenched in the region. Transnational civil society can further catalyse change by advocating regional cooperation and demanding action, accountability, and compliance to international laws and agreements.

Similarly, the private sector can play a transformative role through innovation, entrepreneurship, and technological solutions. By developing and adopting cleaner industrial processes, sustainable farming practices, and cost-effective pollution control technologies, businesses and enterprises can make the transition to clean air practical and profitable.

In sum, a three-pronged approach is needed:

Clean air must now become a political priority, a governance issue, and a central political discourse—not just in Nepal but throughout South Asia.

Read More Stories

Kathmandu’s decay: From glorious past to ominous future

Kathmandu: The legend and the legacy Legend about Kathmandus evolution holds that the...

Kathmandu - A crumbling valley!

Valleys and cities should be young, vibrant, inspiring and full of hopes with...

As of now, Karnahaang will be known as Darasingh and is pardoned for...